"Okay, you see this little bean that destroyed itself and gave you a new sprout?... Put that in the soil so you can get a hundred other ones, and then put one of those in the soil so you can get a thousand." — Ron Finley, educator, activist, gangster gardener

Seeds are magical things. Each seed contains all the information it needs to grow into an entire plant, providing food and shelter and even producing "offspring" in the form of next season's seeds. Over the years, seeds adapt to their environment, the changing weather cycles and soil types, becoming better candidates for success in their little corner of the world.

The crops we grow today are the product of millions of years of natural selection, as well as millennia of human stewardship around the globe. During the last century, private interests, corporate consolidation and some very questionable court rulings have changed how seeds are grown, saved, shared and sold.

In the early 20th century, plants and seeds were considered natural creations. As products of nature, not of man, they could not be patented. Since that time, a lot has changed. Today, restrictive seed patenting is the norm, and 60% of the world's seed supply is owned by just 4 chemical companies. This has major implications for farmers who have traditionally saved seed from year to year. When it comes to GMOs, Jack Kloppenburg remarks in his book First the Seed, "farmers no longer buy seeds, they rent that seed."

How did we get from there to here?

Who owns plants?

"It would be 'unreasonable and impossible' to allow patents upon the trees of the forest and the plants of the earth." — U.S. Commissioner of Patents, 1889

Patents are a kind of intellectual property right meant to promote and protect innovation. They provide legal ownership to the inventors of new and useful discoveries for a limited period of time. Different classes of patents apply to different types of inventions. The largest category is "utility patents," which can apply to "any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof." Many of the appliances, gadgets and gizmos that we use in modern life would have been covered by utility patents when they were invented.

Ownership of living organisms like plants, however, was viewed differently at the beginning of the last century. Living organisms were considered products of nature and not eligible for patents. The work of plant breeders and seed producers is unique: It's a combination of the products and processes of nature and human intervention.

In time, provisions were made to offer some protection to plant breeders. Plant patents were first introduced in 1930. However, seed varieties — which reproduce sexually and include many of our common food crops — were not eligible for plant patents. It wasn't until the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970 (PVPA) that seed breeders had some protection for the varieties they produced. The PVPA walks a fine line: While it offers protection to seed breeders, the Act acknowledges that continued innovation depends on the plants and seeds being shared. To keep the practice of plant breeding moving forward, neither plant patents nor plant variety protections provide the kind of exclusive power that utility patents — which we mentioned above in relation to appliances and gadgets — do. According to legal scholar Malla Pollack, the laws that protect plant breeders have two significant exceptions: "one allowing farmers to save seed for later planting and one allowing research. "

Under the PVPA, seed varieties can, in some instances, be shared. Other researchers can build on the earlier work, and farmers can save seeds for planting the next year — a practice that bolsters their autonomy and builds a supply of regionally-adapted seeds that offer some of the best genetic traits for resilience and high yields.

Genetically modified organisms and the techniques used to create them are eligible for the much more restrictive utility patents. This classification prohibits farmers from saving or breeding the seed and keeps the genetic material private for the duration of the patent.

The legal basis for this decision is all thanks to General Electric, an oil spill and a genetically engineered bacteria.

How GMOs changed the landscape

In the 1970s, microbiologist and General Electric employee Dr. Ananda Chakrabarty created a genetically engineered bacteria capable of breaking down crude oil. Dr. Chakrabarty saw a potential use for this bacteria in cleaning up oil spills. His quest to patent his invention inadvertently set the stage for the privatization of the seed supply.

Dr. Chakrabarty's GMO bacteria was initially denied a patent because bacteria is a living organism. Living organisms were considered a "product of nature" by the U.S. Patent Office. The only patent class that permitted living organisms was plant patents, and the GMO bacteria didn't fit in there. Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided the GMO bacteria qualified as a "new composition of matter" — one of the clauses describing a utility patent — because of the genetic modification. The genetically engineered bacteria was a living organism, but because of the modification to its DNA, it was no longer in a state of nature.

This decision established human-made organisms as patentable, and just as importantly, patentable under the restrictive utility class. The restrictions of utility patents are why the genetic material is held privately — unavailable for public research — for the duration of the patent, and why farmers cannot save GMO seed.

Protecting GMOs with utility patents also reveals a kind of duplicity in the rhetoric of the chemical companies that create them: To investors and patent offices, companies emphasize the novelty and innovation of GMOs to secure funding and utility patents, while to regulatory boards and the general public, they argue the opposite, marketing GMOs as an extension of traditional breeding techniques.

To one audience, they cry, "It's totally new!"

To another, "It's totally natural!"

It's no wonder chemical companies face a skeptical public.

Privatization and monopoly in the food system

"The courts and the PTO [Patent and Trademark Office] have given a few large businesses the power to close down most independent research on basic food crops." — Malla Pollack

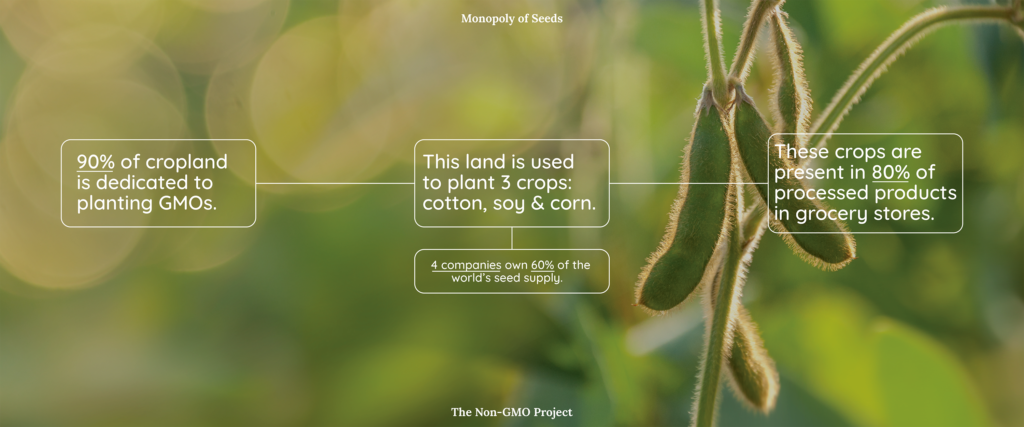

For all the resources deployed to develop GMO crops and the fortunes made from marketing them, there are at this time a limited number of commercially available varieties owned by a handful of corporations. This small group casts a vast shadow across the agricultural land of North America — 90% of U.S. cropland is dedicated to just 3 commodity GMO crops (corn, cotton and soy). From there, GMO crops are processed and find their way into an estimated 80% of the conventional processed foods. This produces a very unbalanced kind of control of food and resources:

This monopolization means that our food systems — and the ecosystems they rely upon — are based on a limited number of crops. The more reliant we are on that limited number of crops, the more our fates are tied to theirs. As the effectiveness of herbicide-tolerant and pest-resistant crops fail, it's well past time to diversify our food system portfolio. Monopolies do not foster innovation, and chemical corporations show no signs of loosening their grip.

Some of the most powerful corporations in the world routinely harass farmers, seed savers and breeders around the globe as they try to operate outside the monopolized and privatized seed supply. Harassment can come in the form of legal action, as has been extensively reported by the Center for Food Safety. There are also cases of casual intimidation, such as when a major corporation mailed baseless patent infringement notices to small seed companies across the U.S.; or in another instance when good faith efforts by small farmers to resolve GMO contamination risks were rebuffed by corporate lawyers.

What you can do

Promoting seed sovereignty and biodiversity are essential to creating a truly resilient and healthy food system that works for everybody. There are many organizations — including the Non-GMO Project — working to restore farmers' rights. An obvious first step is to avoid GMOs by looking for the Butterfly — after all, we can choose how our food is made. Here are some additional resources:

- The best way to fall in love with seeds is to watch them do their thing, and this is the perfect time of year for planting. The Open Source Seed Initiative lists seed producers who are committed to sharing and building our genetic inheritance.

- Visit the Seed Savers Exchange to find and share seeds in the public domain or to find a seed library (like a regular library, but with seeds instead of books) in your area.

- Follow the work of organizations like the Organic Seed Alliance and A Growing Culture to find out more about farmers' rights and seed sovereignty around the world.

For all our craftiness and innovation, it's worth remembering that the seeds didn't start with us, nor will they end with us. We hold them in our hands for a while. If we're truly lucky, we watch them grow.